Which Metalworking Technique Was Used To Decorate Bronze Etruscan Cistae

ROMAN POTTERY

ceramic lamp Roman pottery included red earthenware known as Samian ware and blackness pottery known every bit Etruscan ware, which was different than the pottery actually made by the Etruscans. The Roman pioneered the use of ceramics for things similar bathtubs and drainage pipes.

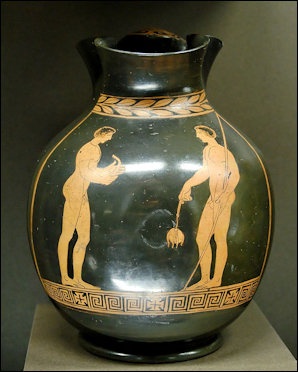

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "For near 300 years, Greek cities forth the coasts of southern Italy and Sicily regularly imported their fine ware from Corinth and, subsequently, Athens. By the third quarter of the fifth century B.C., however, they were acquiring red-figured pottery of local manufacture. Equally many of the craftsmen were trained immigrants from Athens, these early South Italian vases were closely modeled after Attic prototypes in both shape and design. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

"By the finish of the fifth century B.C., Cranium imports ceased every bit Athens struggled in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War in 404 B.C. The regional schools of South Italian vase painting—Apulian, Lucanian, Campanian, Paestan—flourished between 440 and 300 B.C. In full general, the fired clay shows much greater variation in color and texture than that which is found in Attic pottery. A distinct preference for added color, especially white, yellow, and red, is characteristic of South Italian vases in the fourth century B.C. Compositions, particularly those on Apulian vases, tend to exist grandiose, with statuesque figures shown in several tiers. There is also a fondness for depicting architecture, with the perspective not always successfully rendered. \^/

"Near from the get-go, South Italian vase painters tended to favor elaborate scenes from daily life, mythology, and Greek theater. Many of the paintings bring to life stage practices and costumes. A detail fondness for the plays of Euripides testifies to the continued popularity of Attic tragedy in the fourth century B.C. in Magna Graecia. In general, the images frequently testify one or two highlights of a play, several of its characters, and oft a pick of divinities, some of which may or may not exist directly relevant. Some of the liveliest products of Southward Italian vase painting in the 4th century B.C. are the and so-called phlyax vases, which depict comics performing a scene from a phlyax, a type of farce play that developed in southern Italy. These painted scenes bring to life the boisterous characters with grotesque masks and padded costumes."

Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 manufactures) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Organized religion and Myths (35 manufactures) factsanddetails.com; Aboriginal Roman Fine art and Culture (33 manufactures) factsanddetails.com; Aboriginal Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economic science (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near Due east Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Aboriginal History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Belatedly Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; "Outlines of Roman History" forumromanum.org; "The Private Life of the Romans" forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.united kingdom/history; Perseus Projection - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans; The Cyberspace Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.britain; Oxford Classical Art Research Heart: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/near-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Internet Classics Annal kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Ancient Rome resource for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.annal.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Matriarch /web.archive.org ; Un of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Funerary Vases in Southern Italy and Sicily

Co-ordinate to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "Most extant Due south Italian vases have been discovered in funerary contexts, and a significant number of these vases were likely produced solely equally grave goods. This role is demonstrated by the vases of various shapes and sizes that are open at the bottom, rendering them useless for the living. Ofttimes the vases with open bottoms are monumentalized shapes, peculiarly volute-kraters, amphorae, and loutrophoroi, which began to be produced in the 2nd quarter of the 4th century B.C. The perforation at the bottom prevented impairment during firing and also allowed them to serve as grave markers. Liquid libations offered to the dead were poured through the containers into the soil containing the deceased's remains. Evidence for this practice exists in the cemeteries of Tarentum (modern Taranto), the merely pregnant Greek colony in the region of Apulia (modernistic Puglia).

amphorae, mutual and used for storing nutrient, wine and other things

"Most surviving examples of these monumental vases are not institute in Greek settlements, only in sleeping room tombs of their Italic neighbors in northern Apulia. In fact, the loftier demand for large-calibration vases among the native peoples of the region seems to have spurred Tarentine émigrés to establish vase painting workshops by the mid-fourth century B.C. at Italic sites such equally Ruvo, Canosa, and Ceglie del Campo. \^/

"The imagery painted on these vases, rather than their physical structure, all-time reflects their intended sepulchral function. The almost common scenes of daily life on South Italian vases are depictions of funerary monuments, normally flanked past women and nude youths bearing a diverseness of offerings to the grave site such every bit fillets, boxes, perfume vessels (alabastra), libation bowls (phialai), fans, bunches of grapes, and rosette chains. When the funerary monument includes a representation of the deceased, there is non necessarily a strict correlation between the types of offerings and the gender of the commemorated individual(due south). For instance, mirrors, traditionally considered a female person grave good in earthworks contexts, are brought to monuments depicting individuals of both genders. \^/

"The preferred blazon of funerary monument painted on vases varies from region to region within southern Italian republic. On rare occasions, the funerary monument may consist of a statue, presumably of the deceased, standing on a elementary base of operations. Within Campania, the grave monument of choice on vases is a simple stone slab (stele) on a stepped base. In Apulia, vases are decorated with memorials in the form of a small templelike shrine called a naiskos. The naiskoi usually contain within them one or more figures, understood as sculptural depictions of the deceased and their companions. The figures and their architectural setting are usually painted in added white, presumably to place the material as rock. Added white to represent a statue may also be seen on an Apulian column-krater where an artist applied colored pigment to a marble statue of Herakles. Furthermore, painting figures within naiskoi in added white differentiates them from the living figures around the monument who are rendered in red-figure. There are exceptions to this practice—red-figure figures inside naiskoi may represent terracotta bronze. Every bit Southward Italy lacks indigenous marble sources, the Greek colonists became highly skilled coroplasts, able to render even lifesized figures in clay. \^/

"Past the mid-fourth century B.C., awe-inspiring Apulian vases typically presented a naiskos on one side of the vase and a stele, like to those on Campanian vases, on the other. It was as well popular to pair a naiskos scene with a complex, multifigured mythological scene, many of which were inspired past tragic and epic subjects. Effectually 330 B.C., a strong Apulianizing influence became evident in Campanian and Paestan vase painting, and naiskos scenes began appearing on Campanian vases. The spread of Apulian iconography may exist continued to the military activity of Alexander the Molossian, uncle of Alexander the Great and king of Epirus, who was summoned past the city of Tarentum to atomic number 82 the Italiote League in efforts to reconquer former Greek colonies in Lucania and Campania. \^/

"In many naiskoi, vase painters attempted to render the architectural elements in iii-dimensional perspective, and archaeological prove suggests that such monuments existed in the cemeteries of Tarentum, the last of which stood until the late nineteenth century. The surviving evidence is fragmentary, equally modern Taranto covers much of the ancient burial grounds, but architectural elements and sculptures of local limestone are known. The dating of these objects is controversial; some scholars place them as early on every bit 330 B.C., while others date them all during the second century B.C. Both hypotheses postdate most, if not all, of their counterparts on vases. On a fragmentary piece in the Museum's collection, which decorated either the base or back wall of a funerary monument, a pilos helmet, sword, cloak, and cuirass are suspended on the background. Like objects hang within the painted naiskoi. Vases that testify naiskoi with architectural sculpture, such every bit patterned bases and figured metopes, accept parallels in the remains of limestone monuments. \^/

southern Italian vase painting of athletes

"In a higher place the funerary monuments on monumental vases there is frequently an isolated caput, painted on the cervix or shoulder. The heads may ascension from a bell-bloom or acanthus leaves and are ready within a lush surround of flowering vines or palmettes. Heads within leaf appear with the primeval funerary scenes on South Italian vases, beginning in the second quarter of the 4th century B.C. Typically the heads are female, just heads of youths and satyrs, as well as those with attributes such as wings, a Phrygian cap, a polos crown, or a nimbus, also appear. Identification of these heads has proven difficult, every bit there is only ane known instance, now in the British Museum, whose name is inscribed (chosen "Aura"—"Breeze"). No surviving literary works from aboriginal southern Italy illuminate their identity or their function on the vases. The female person heads are drawn in the aforementioned manner as their full-length counterparts, both mortal and divine, and are commonly shown wearing a patterned headdress, a radiate crown, earrings, and a necklace. Even when the heads are bestowed with attributes, their identity is indeterminate, allowing a diversity of possible interpretations. More than narrowly defining attributes are very rare and do little to identify the aspect-less majority. The isolated head became very popular as primary decoration on vases, particularly those of small calibration, and by 340 B.C., information technology was the unmarried well-nigh common motif in South Italian vase painting. The relation of these heads, set in rich vegetation, to the grave monuments below them suggests they are strongly connected to fourth-century B.C. concepts of a hereafter in southern Italy and Sicily. \^/

"Although the production of Due south Italian red-figure vases ceased around 300 B.C., making vases purely for funerary use continued, most notably at Centuripe, a town in eastern Sicily near Mount Etna. The numerous polychrome terracotta figurines and vases of the third century B.C. were decorated with tempera colors after firing. They were further elaborated with complex vegetal and architecturally inspired relief elements. I of the most common shapes, a footed dish chosen a lekanis, was often constructed of contained sections (foot, bowl, lid, chapeau knob, and finial), resulting in few complete pieces today. On some pieces, such equally the lebes in the Museum's collection, the lid was made in one slice with the body of the vase, and then that information technology could not function as a container. The construction and fugitive decoration of Centuripe vases point their intended role equally grave appurtenances. The painted imagery relates to weddings or the Dionysiac cult, whose mysteries enjoyed bully popularity in southern Italia and Sicily, presumably due to the blissful afterlife promised to its initiates.

Five Wares of South Italian Vase Painting

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "South Italian vases are ceramics, mostly busy in the reddish-figure technique, that were produced past Greek colonists in southern Italy and Sicily, the region often referred to every bit Magna Graecia or "Great Greece." Ethnic production of vases in imitation of cherry-figure wares of the Greek mainland occurred sporadically in the early fifth century B.C. inside the region. Nevertheless, around 440 B.C., a workshop of potters and painters appeared at Metapontum in Lucania and presently later at Tarentum (mod-solar day Taranto) in Apulia. It is unknown how the technical knowledge for producing these vases traveled to southern Italia. Theories range from Athenian participation in the founding of the colony of Thurii in 443 B.C. to the emigration of Athenian artisans, mayhap encouraged by the onset of the Peloponnesian State of war in 431 B.C. The war, which lasted until 404 B.C., and the resulting decline of Athenian vase exports to the west were certainly important factors in the successful continuation of cherry-figure vase production in Magna Graecia. The manufacture of South Italian vases reached its zenith between 350 and 320 B.C., then gradually tapered off in quality and quantity until simply afterwards the shut of the fourth century B.C. [Source: Keely Heuer, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, December 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

Lucanian vase

"Modern scholars have divided South Italian vases into five wares named after the regions in which they were produced: Lucanian, Apulian, Campanian, Paestan, and Sicilian. South Italian wares, dissimilar Attic, were not widely exported and seem to have been intended solely for local consumption. Each fabric has its own distinct features, including preferences in shape and decoration that make them identifiable, even when exact provenance is unknown. Lucanian and Apulian are the oldest wares, established within a generation of each other. Sicilian cherry-red-effigy vases appeared non long after, just earlier 400 B.C. By 370 B.C., potters and vase painters migrated from Sicily to both Campania and Paestum, where they founded their respective workshops. Information technology is thought that they left Sicily due to political upheaval. After stability returned to the island around 340 B.C., both Campanian and Paestan vase painters moved to Sicily to revive its pottery industry. Unlike in Athens, almost none of the potters and vase painters in Magna Graecia signed their work, thus the bulk of names are modern designations. \^/

"Lucania, corresponding to the "toe" and "instep" of the Italian peninsula, was dwelling house to the primeval of the South Italian wares, characterized by the deep ruby-orange color of its dirt. Its about distinctive shape is the nestoris, a deep vessel adopted from a native Messapian shape with upswung side handles sometimes decorated with disks. Initially, Lucanian vase painting very closely resembled contemporary Attic vase painting, as seen on a finely drawn bitty skyphos attributed to the Palermo Painter. Favored iconography included pursuit scenes (mortal and divine), scenes of daily life, and images of Dionysos and his adherents. The original workshop at Metaponto, founded by the Pisticci Painter and his two chief colleagues, the Cyclops and Amykos Painters, disappeared between 380 and 370 B.C.; its leading artists moved into the Lucanian hinterland to sites such as Roccanova, Anzi, and Armento. Afterward this indicate, Lucanian vase painting became increasingly provincial, reusing themes from earlier artists and motifs borrowed from Apulia. With the move to more remote parts of Lucania, the color of the clay also changed, best exemplified in the piece of work of the Roccanova Painter, who applied a deep pink wash to heighten the light colour. After the career of the Primato Painter, the last of the notable Lucanian vase painters, active between ca. 360 and 330 B.C., the ware consisted of poor imitations of his manus until the last decades of the fourth century B.C., when production ceased. \^/

"More half of extant Southward Italian vases come from Apulia (modern Puglia), the "heel" of Italy. These vases were originally produced in Tarentum, the major Greek colony in the region. The demand became so dandy amidst the native peoples of the region that by the mid-4th century B.C., satellite workshops were established in Italic communities to the north such as Ruvo, Ceglie del Campo, and Canosa. A distinctive shape of Apulia is the knob-handled patera, a low-footed, shallow dish with two handles rising from the rim. The handles and rim are elaborated with mushroom-shaped knobs. Apulia is also distinguished by its product of monumental shapes, including the volute-krater, the amphora, and the loutrophoros. These vases were primarily funerary in role. They are decorated with scenes of mourners at tombs and elaborate, multifigured mythological tableaux, a number of which are rarely, if e'er, seen on the vases of the Greek mainland and are otherwise only known through literary evidence. Mythological scenes on Apulian vases are depictions of ballsy and tragic subjects and were likely inspired past dramatic performances. Sometimes these vases provide illustrations of tragedies whose surviving texts, other than the title, are either highly fragmentary or entirely lost. These large-scale pieces are categorized as "Ornate" in style and feature elaborate floral ornament and much added color, such equally white, xanthous, and red. Smaller shapes in Apulia are typically decorated in the "Plainly" mode, with simple compositions of 1 to five figures. Popular subjects include Dionysos, every bit both god of theater and wine, scenes of youths and women, frequently in the company of Eros, and isolated heads, commonly that of a woman. Prominent, peculiarly on column-kraters, is the depiction of the indigenous peoples of the region, such as the Messapians and Oscans, wearing their native apparel and armor. Such scenes are usually interpreted as an arrival or departure, with the offering of a libation. Counterparts in bronze of the wide belts worn past the youths on a column-krater attributed to the Rueff Painter have been found in Italic tombs. The greatest output of Apulian vases occurred between 340 and 310 B.C., despite political upheaval in the region at the fourth dimension, and about of the surviving pieces can be assigned to its two leading workshops—1 led past the Darius and Underworld Painters and the other by the Patera, Ganymede, and Baltimore Painters. Later on this floruit, Apulian vase painting declined chop-chop. \^/

Lucian crater with a symposium scene attributed to Python

"Campanian vases were produced by Greeks in the cities of Capua and Cumae, which were both under native control. Capua was an Etruscan foundation that passed into the hands of Samnites in 426 B.C. Cumae, one of the primeval of the Greek colonies in Magna Graecia, was founded on the Bay of Naples by Euboeans no later than 730–720 B.C. It, too, was captured past native Campanians in 421 B.C., but Greek laws and customs were retained. The workshops of Cumae were founded slightly later than those of Capua, around the middle of the 4th century B.C. Notably absent in Campania are awe-inspiring vases, possibly i of the reasons why in that location are fewer mythological and dramatic scenes. The virtually distinctive shape in the Campanian repertoire is the bail-amphora, a storage jar with a single handle that arches over the mouth, often pierced at its meridian. The color of the fired clay is a pale buff or light orange-xanthous, and a pink or red wash was oftentimes painted over the unabridged vase before information technology was busy to enhance the color. Added white was used extensively, particularly for the exposed flesh of women. While vases of the Sicilian emigrants who settled in Campania are found at a number of sites in the region, it is the Cassandra Painter, the caput of a workshop in Capua between 380 and 360 B.C., who is credited as being the primeval Campanian vase painter. Close to him in mode is the Spotted Rock Painter, named for an unusual characteristic of Campanian vases that incorporates the expanse'southward natural topography, shaped past volcanic activity. Depicting figures seated upon, leaning against, or resting a raised foot on rocks and rock piles was a common practice in South Italian vase painting. Simply on Campanian vases, these rocks are often spotted, representing a form of igneous breccia or agglomerate, or they take the sinuous forms of cooled lava flows, both of which were familiar geological features of the landscape. The range of subjects is relatively limited, the most characteristic being representations of women and warriors in native Osco-Samnite dress. The armor consists of a three-deejay breastplate and helmet with a alpine vertical feather on both sides of the head. Local dress for women consists of a brusque cape over the garment and a headdress of draped material, rather medieval in appearance. The figures participate in libations for departing or returning warriors also as in funerary rites. These representations are comparable to those found in painted tombs of the region as well equally at Paestum. Also pop in Campania are fish plates, with swell detail paid to the dissimilar species of sea life painted on them. Around 330 B.C., Campanian vase painting became subject to a strong Apulianizing influence, probably due to the migration of painters from Apulia to both Campania and Paestum. In Capua, production of painted vases ended effectually 320 B.C., but continued in Cumae until the finish of the century. \^/

"The city of Paestum is located in the northwest corner of Lucania, but stylistically its pottery is closely connected to that of neighboring Campania. Like Cumae, it was a former Greek colony, conquered by the Lucanians around 400 B.C. While Paestan vase painting does not feature whatsoever unique shapes, it is ready apart from the other wares for being the only one to preserve the signatures of vase painters: Asteas and his close colleague Python. Both were early on, accomplished, and highly influential vase painters who established the ware's stylistic canons, which inverse only slightly over time. Typical features include dot-stripe borders along the edges of drapery and the so-called framing palmettes typical on large- or medium-scaled vases. The bell-krater is a peculiarly favored shape. Scenes of Dionysos predominate; mythological compositions occur, only tend to be overcrowded, with boosted busts of figures in the corners. The most successful images on Paestan vases are those of comedic performances, oft termed "phlyax vases" after a type of farce adult in southern Italia. However, testify indicates an Athenian origin for at least some of these plays, which feature stock characters in grotesque masks and exaggerated costumes. Such phlyax scenes are likewise painted on Apulian vases. \^/

"Sicilian vases tend to be small-scale in scale and popular shapes include the bottle and the skyphoid pyxis. The range of subjects painted on vases is the most limited of all the South Italian wares, with most vases showing the feminine world: bridal preparations, toilet scenes, women in the company of Nike and Eros or simply by themselves, ofttimes seated and gazing expectantly upwardly. After 340 B.C., vase product seems to have been concentrated in the area of Syracuse, at Gela, and effectually Centuripe about Mount Etna. Vases were also produced on the island of Lipari, merely off the Sicilian declension. Sicilian vases are striking for their ever increasing use of added colors, peculiarly those found on Lipari and near Centuripe, where in the third century B.C. there was a thriving manufacture of polychrome ceramics and figurines.

Praenestine Cistae

Praenestine Cistae depicting Helen of Troy and Paris

Maddalena Paggi of the The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art wrote: "Praenestine cistae are sumptuous metal boxes generally of cylindrical shape. They accept a lid, figurative handles, and feet separately manufactured and fastened. Cistae are covered with incised decoration on both body and chapeau. Trivial studs are placed at equal distance at a 3rd of the cista'south height all around, regardless of the incised decoration. Small metal bondage were attached to these studs and probably used to elevator the cistae. [Source: Maddalena Paggi, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

"As funerary objects, cistae were placed in the tombs of the fourth-century necropolis at Praeneste. This town, located 37 kilometers southeast of Rome in the region of Latius Vetus, was an Etruscan outpost in the seventh century B.C., equally the wealth of its princely burials indicates. Excavations conducted at Praeneste in the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century were primarily aimed at the recovery of these precious-metallic objects. The subsequent demand for cistae and mirrors caused the systematic plundering of the Praenestine necropolis. Cistae acquired value and importance in the antiquities market place, which also encouraged the production of forgeries. \^/

"Cistae are a very heterogeneous group of objects, but vary in terms of quality, narrative, and size. Artistically, cistae are complex objects in which unlike techniques and styles coexist: engraved ornament and cast attachments seem to be the result of different technical expertise and traditions. Collaboration of craftsmanship was required for their 2-phase manufacturing process: the decoration (casting and engraving) and the associates. \^/

"The virtually famous cista and the start to be discovered is the Ficoroni presently in the Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome, named after the well-known collector Francesco de' Ficoroni (1664–1747), who kickoff owned information technology. Although the cista was constitute at Praeneste, its dedicatory inscription indicates Rome as the place of product: NOVIOS PLVTIUS MED ROMAI FECID/ DINDIA MACOLNIA FILEAI DEDIT (Novios Plutios made me in Rome/ Dindia Macolnia gave me to her daughter). These objects have often been taken as examples of middle Republican Roman art. However, the Ficoroni inscription remains the only evidence for this theory, while there is aplenty evidence for a local production at Praeneste. \^/

"The high-quality Praenestine cistae often adhere to the classical ideal. The proportions, limerick, and way of the figures indeed present shut connections and noesis of Greek motifs and conventions. The engraving of the Ficoroni cista portrays the myth of the Argonauts, the conflict between Pollux and Amicus, in which Pollux is victorious. The engravings on the Ficoroni cista have been viewed as a reproduction of a lost 5th-century painting by Mikon. Difficulties remain, however, in finding precise correspondences betwixt Pausanias' description of such a painting and the cista. \^/

"The function and use of Praenestine cistae are still unresolved questions. Nosotros tin can safely say that they were used every bit funerary objects to accompany the deceased into the next globe. It has likewise been suggested that they were used equally containers for toiletries, like a beauty case. Indeed, some recovered examples independent small objects such as tweezers, brand-up boxes, and sponges. The large size of the Ficoroni cista, nevertheless, excludes such a function and points toward a more ritualistic use. \^/

Glass Making

blowing drinking glass

Modern glass bravado began in 50 B.C. with the Romans, just origins of glass making go back fifty-fifty further. Pliny the Elder attributed the discovery to Phoenician sailors who placed a sandy pot on some lumps of alkali embalming pulverization from their ship. This provided the three ingredients needed for glass making: heat, sand and lime. Although it is interesting story, it is far from truthful.

The oldest glass and then far discovered is from site in Mesopotamia, dated to 3000 B.C., and glass in all likelihood was made before that. The ancient Egyptians produced fine pieces of glass. The eastern Mediterranean produced especially beautiful drinking glass because the materials were of fine quality.

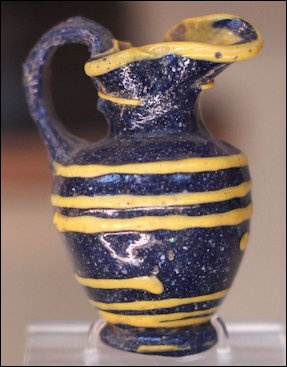

Effectually the 6th century B.C. the "cadre glass method" of glass making from Mesopotamia and Arab republic of egypt was revived under the influence of Greek ceramics makers in Phoenicia in the eastern Mediterranean and so was widely traded by Phoenician merchants. During the Hellenistic period, high quality pieces were created using a multifariousness of techniques, including the cast glass and mosaic glass.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "Core-formed and cast glass vessels were first produced in Egypt and Mesopotamia as early as the fifteenth century B.C., just only began to be imported and, to a lesser extent, made on the Italian peninsula in the mid-showtime millennium B.C. Glassblowing developed in the Syro-Palestinian region in the early starting time century B.C. and is thought to have come to Rome with craftsmen and slaves after the area's annexation to the Roman earth in 64 B.C. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Roman Glass Making

The Romans fabricated drinking cups, vases, bowls, storage jars, decorative items and other object in a variety of shapes and colors. using blown glass. The Roman, wrote Seneca, read "all the books in Rome" by peering at them through a glass globe. The Romans made sheet glass only never perfected the process partly because windows weren't considered necessary in the relatively warm Mediterranean climate.

The Romans made a number of advancements, the most notable of which was mold-blown drinking glass, a technique still used today. Developed in the eastern Mediterranean in the 1st century B.C., this new technique allowed drinking glass to be made transparent and in a wide multifariousness of shapes and sizes. It also allowed drinking glass to be mass produced, making glass something that ordinary people could afford besides as the rich. The use of mold-blown glass spread throughout the Roman empire and was influenced past different cultures and arts.

Roman drinking glass amphora With the core-form mold-diddled technique, globs of glass are heated in a furnace until they go glowing orange orbs. Glass threads are wound around a cadre with a handling piece of metal. Craftsmen so roll, blow and spin the drinking glass to get the shapes they want.

With the casting technique, a mold is formed with a model. The mold is filled with crushed or powdered drinking glass and heated. Subsequently cooling downwardly, the plank is removed from the mold, and the interior cavity is drilled and exterior is well cut. With the mosaic glass technique, rods of glass are fused, drawn and cutting into canes. These canes are bundled in a mold and heated to make a vessel.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art: "At the tiptop of its popularity and usefulness in Rome, glass was nowadays in nearly every aspect of daily life—from a lady's morn toilette to a merchant's afternoon business dealings to the evening cena, or dinner. Glass alabastra, unguentaria, and other small bottles and boxes held the various oils, perfumes, and cosmetics used by virtually every member of Roman gild. Pyxides often contained jewelry with drinking glass elements such as beads, cameos, and intaglios, made to imitate semi-precious stone like carnelian, emerald, stone crystal, sapphire, garnet, sardonyx, and amethyst. Merchants and traders routinely packed, shipped, and sold all manner of foodstuffs and other goods beyond the Mediterranean in glass bottles and jars of all shapes and sizes, supplying Rome with a cracking diversity of exotic materials from furthermost parts of the empire. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

"Other applications of drinking glass included multicolored tesserae used in elaborate flooring and wall mosaics, and mirrors containing colorless glass with wax, plaster, or metal bankroll that provided a cogitating surface. Glass windowpanes were first made in the early purple menstruation, and used most prominently in the public baths to prevent drafts. Because window glass in Rome was intended to provide insulation and security, rather than illumination or equally a mode of viewing the world outside, little, if any, attending was paid to making it perfectly transparent or of even thickness. Window drinking glass could be either cast or diddled. Cast panes were poured and rolled over flat, usually wooden molds laden with a layer of sand, and then footing or polished on 1 side. Blown panes were created by cutting and flattening a long cylinder of diddled glass."

Development of Roman Drinking glass

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: " Past the fourth dimension of the Roman Democracy (509–27 B.C.), such vessels, used as tableware or equally containers for expensive oils, perfumes, and medicines, were common in Etruria (modernistic Tuscany) and Magna Graecia (areas of southern Italy including modern Campania, Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily). However, there is very little evidence for like glass objects in primal Italian and Roman contexts until the mid-first century B.C. The reasons for this are unclear, only it suggests that the Roman drinking glass industry sprang from almost nothing and developed to total maturity over a couple of generations during the beginning half of the offset century A.D. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

glass jug

"Doubtless Rome'due south emergence every bit the dominant political, war machine, and economic ability in the Mediterranean world was a major gene in alluring skilled craftsmen to set up workshops in the city, simply equally of import was the fact that the establishment of the Roman industry roughly coincided with the invention of glassblowing. This invention revolutionized ancient drinking glass production, putting information technology on a par with the other major industries, such equally that of pottery and metalwares. Also, glassblowing allowed craftsmen to make a much greater multifariousness of shapes than earlier. Combined with the inherent bewitchery of glass—it is nonporous, translucent (if non transparent), and odorless—this adaptability encouraged people to alter their tastes and habits, so that, for example, glass drinking cups speedily supplanted pottery equivalents. In fact, the production of certain types of native Italian clay cups, bowls, and beakers declined through the Augustan period, and by the mid-offset century A.D. had ceased altogether. \^/

"Notwithstanding, although blown glass came to dominate Roman glass production, it did not altogether supplant bandage glass. Especially in the first half of the first century A.D., much Roman glass was made by casting, and the forms and decoration of early Roman bandage vessels demonstrate a strong Hellenistic influence. The Roman drinking glass industry owed a corking bargain to eastern Mediterranean glassmakers, who first developed the skills and techniques that fabricated glass so popular that it tin can exist found on every archaeological site, non only throughout the Roman empire but too in lands far across its frontiers. \^/

Bandage Glass Versus Blown Glass in Ancient Rome

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "Although the core-formed industry dominated glass industry in the Greek world, casting techniques also played an important role in the development of glass in the ninth to fourth centuries B.C. Cast glass was produced in two basic ways—through the lost-wax method and with various open and plunger molds. The well-nigh mutual method used past Roman glassmakers for virtually of the open-grade cups and bowls in the first century B.C. was the Hellenistic technique of sagging glass over a convex "former" mold. However, diverse casting and cutting methods were continuously utilized equally style and popular preference demanded. The Romans also adopted and adapted various color and design schemes from the Hellenistic glass traditions, applying such designs equally network drinking glass and gold-ring glass to novel shapes and forms. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Section of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

ribbed mosaic glass bowl

"Distinctly Roman innovations in material styles and colors include marbled mosaic glass, short-strip mosaic glass, and the crisp, lathe-cut profiles of a new breed of fine equally monochrome and colorless tablewares of the early empire, introduced around 20 A.D. This class of glassware became one of the most prized styles considering it closely resembled luxury items such as the highly valued rock crystal objects, Augustan Arretine ceramics, and bronze and silver tablewares and so favored by the aristocratic and prosperous classes of Roman guild. In fact, these fine wares were the only drinking glass objects continually formed via casting, even up to the as Late Flavian, Trajanic, and Hadrianic periods (96–138 A.D.), after glassblowing superceded casting as the dominant method of glassware manufacture in the early on kickoff century A.D. \^/

"Glassblowing adult in the Syro-Palestinian region in the early start century B.C. and is thought to have come to Rome with craftsmen and slaves after the surface area's annexation to the Roman world in 64 B.C. The new applied science revolutionized the Italian glass industry, stimulating an enormous increment in the range of shapes and designs that glassworkers could produce. A glassworker'due south creativity was no longer bound by the technical restrictions of the laborious casting process, as blowing immune for previously unparalleled versatility and speed of manufacture. These advantages spurred a rapid evolution of style and form, and experimentation with the new technique led craftsmen to create novel and unique shapes; examples exist of flasks and bottles shaped like foot sandals, wine barrels, fruits, and even helmets and animals. Some combined blowing with drinking glass-casting and pottery-molding technologies to create the then-called mold-blowing procedure. Further innovations and stylistic changes saw the continued use of casting and gratis-blowing to create a variety of open and closed forms that could then be engraved or facet-cut in any number of patterns and designs." \^/

Roman Glass Masterpieces

The highest toll ever paid for drinking glass is $1,175,200 for a Roman drinking glass-cup from A.D. 300, measuring 7 inches in diameter and four inches in elevation, sold at Sotheby'southward in London in June 1979.

One of the almost beautiful pieces of Roman art form is the Portland Vase, a near-blackness cobalt blueish vase that is 9¾ inches tall and vii inches in diameter. Made from glass, but originally thought to have been carved from stone, information technology was made by Roman craftsmen effectually 25 B.C., and featured lovely details reliefs made from milky-white drinking glass. The urn is covered with figures but no 1 is sure who they are. It was found in a A.D. 3rd century tumulus outside of Rome.

Describing the making of a Portland vase, Israel Shenkel wrote in Smithsonian mag: "A gifted artisan may accept first dipped a partially blown globe of the blueish drinking glass into a crucible containing the molten white mass, or he may have formed a "bowl" of white glass and while it was nevertheless malleable diddled the blue vase into information technology. When the layers contracted in cooling, the coefficients of contraction had to be compatible, otherwise the parts would separate or crevice."

"So working from a draining, or a wax or plaster model. a cameo cutter probably incised outlines on the white drinking glass, removed the material around the outlines, and molded details of figures and objects. He most probable used a diversity of tools — cutting wheels, chisels, engravers, polishing wheels polishing stones." Some believe the urn was fabricated by Dioskourides, a gem cutter who worked under Julius Caesar and Augustus.

Roman Cameo Glass

cameo glass prototype of Augustus

Co-ordinate to the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art: "Some of the finest examples of ancient Roman drinking glass are represented in cameo glass, a fashion of glassware that saw just two brief periods of popularity. The bulk of vessels and fragments have been dated to the Augustan and Julio-Claudian periods, from 27 B.C. to 68 A.D., when the Romans made a variety of vessels, big wall plaques, and small jewelry items in cameo glass. While at that place was a brief revival in the 4th century A.D., examples from the later on Roman menses are extremely rare. In the West, cameo glass was not produced once again until the eighteenth century, inspired by the discovery of ancient masterpieces such as the Portland Vase, but in the Eastward, Islamic cameo glass vessels were produced in the 9th and 10th centuries. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org \^/]

"The popularity of cameo glass in early on majestic times was clearly inspired past the gems and vessels carved out of sardonyx that were highly prized in the royal courts of the Hellenistic East. A highly skilled craftsman could cut downwardly layers of overlay glass to such a degree that the background colour would come through successfully duplicating the effects of sardonyx and other naturally veined stones. Notwithstanding, glass had a distinct advantage over semi-precious stones because craftsmen were not constrained by the random patterns of the veins of natural stone but could create layers wherever they needed for their intended subject area. \^/

"It remains uncertain exactly how Roman glassworkers created large cameo vessels, though modern experimentation has suggested two possible methods of industry: "casing" and "flashing." Casing involves placing a globular blank of the groundwork color into a hollow, outer bare of the overlay color, assuasive the 2 to fuse and so blowing them together to form the final shape of the vessel. Flashing, on the other hand, requires that the inner, background blank be shaped to the desired size and form and so dipped into a vat of molten glass of the overlay color, much like a chef would dip a strawberry into melted chocolate. \^/

"The preferred color scheme for cameo glass was an opaque white layer over a dark translucent blueish background, though other color combinations were used and, on very rare occasions, multiple layers were applied to give a stunning polychrome effect. Perhaps the most famous Roman cameo glass vessel is the Portland Vase, now in the British Museum, which is rightly considered i of the crowning achievements of the entire Roman glass manufacture. Roman cameo glass was difficult to produce; the creation of a multilayered matrix presented considerable technical challenges, and the carving of the finished drinking glass required a smashing bargain of skill. The procedure was therefore intricate, costly, and time-consuming, and it has proved extremely challenging for mod glass craftsmen to reproduce. \^/

"Although it owes much to Hellenistic gem and cameo cutting traditions, cameo drinking glass may exist seen as a purely Roman innovation. Indeed, the revitalized creative civilisation of Augustus' Golden Age fostered such creative ventures, and an exquisite vessel of cameo glass would have found a ready market among the imperial family and the elite senatorial families at Rome. \^/

Roman Luxury Glass

Lycurgus color-irresolute cup

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "The Roman drinking glass industry drew heavily on the skills and techniques that were used in other contemporary crafts such as metalworking, jewel cutting, and pottery production. The styles and shapes of much early Roman glass were influenced by the luxury silver and gilded tableware amassed by the upper strata of Roman club in the late Republican and early majestic periods, and the fine monochrome and colorless cast tablewares introduced in the early decades of the showtime century A.D. imitate the crisp, lathe-cutting profiles of their metallic counterparts. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

"The style has been described every bit "aggressively Roman in grapheme" mainly considering information technology lacks whatever close stylistic ties to the Hellenistic cast glass of the late 2d and first centuries B.C. Demand for cast tableware continued through the second and third centuries A.D., and fifty-fifty into the fourth century, and craftsmen kept alive the casting tradition to fashion these high-quality and elegant objects with remarkable skill and ingenuity. Facet-cut, carved, and incised decorations could transform a uncomplicated, colorless plate, bowl, or vase into a masterwork of artistic vision. But engraving and cutting drinking glass was not limited to cast objects alone. There are many examples of both cast and blown glass bottles, plates, bowls, and vases with cutting ornamentation in the Metropolitan Museum'due south collection, and some examples are featured hither. \^/

"Glass cutting was a natural progression from the tradition of gem engravers, who used two basic techniques: intaglio cutting (cutting into the material) and relief cutting (carving out a design in relief). Both methods were exploited by craftsmen working with glass; the latter was used principally and more infrequently to make cameo glass, while the former was widely used both to brand unproblematic cycle-cut decorations, more often than not linear and abstract, and to carve more complex figural scenes and inscriptions. Past the Flavian menstruation (69–96 A.D.), the Romans had begun to produce the beginning colorless glasses with engraved patterns, figures, and scenes, and this new style required the combined skills of more than one craftsman. \^/

"A glass cutter (diatretarius) versed in the use of lathes and drills and who perhaps brought his expertise from a career every bit a jewel cutter, would cutting and decorate a vessel initially cast or diddled past an experienced glassworker (vitrearius). While the technique for cut drinking glass was a technologically simple ane, a high level of workmanship, patience, and time was required to create an engraved vessel of the detail and quality evident in these examples. This also speaks to the increased value and cost of these items. Therefore, even when the invention of glassblowing had transformed glass into a cheap and ubiquitous household object, its potential as a highly prized luxury item did not subtract. \^/

Roman Aureate–Band and Mosaic-Network Glass

golden glass portrait of two young men

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "Amid the start glasswares to appear in significant numbers on Roman sites in Italy are the immediately recognizable and brilliantly colored mosaic glass bowls, dishes, and cups of the late first century B.C. The manufacturing processes for these objects came to Italian republic with Hellenistic craftsmen from the eastern Mediterranean, and these objects retain stylistic similarities with their Hellenistic counterparts. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Fine art, Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, Oct 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

"Mosaic glass objects were manufactured using a laborious and time-consuming technique. Multicolored canes of mosaic glass were created, then stretched to shrink the patterns and either cut beyond into small, round pieces or lengthwise into strips. These were placed together to form a flat circle, heated until they fused, and the resulting disk was then sagged over or into a mold to give the object its shape. Well-nigh all cast objects required polishing on their edges and interiors to smooth the imperfections acquired by the manufacturing process; the exteriors unremarkably did non require further polishing because the rut of the annealing furnace would create a shiny, "burn down polished" surface. Despite the labor-intensive nature of the process, cast mosaic bowls were extremely pop and foreshadowed the entreatment that blown glass was to take in Roman order.

"One of the more prominent Roman adaptations of Hellenistic styles of glassware was the transferred use of gold-band glass on shapes and forms previously unknown to the medium. This type of glass is characterized by a strip of golden drinking glass comprised of a layer of gilded leaf sandwiched between two layers of colorless glass. Typical color schemes also include light-green, blueish, and regal glasses, usually laid side by side and marbled into an onyx pattern earlier being cast or blown into shape.

"While in the Hellenistic menstruum the use of gilded-band drinking glass was mostly restricted to the creation of alabastra, the Romans adjusted the medium for the creation of a variety of other shapes. Luxury items in gold-band glass include lidded pyxides, globular and carinated bottles, and other more exotic shapes such as saucepans and skyphoi (2-handled cups) of various sizes. The prosperous upper classes of Augustan Rome appreciated this glass for its stylistic value and apparent opulence, and the examples shown here illustrate the elegant furnishings gold glass can bring to these forms." \^/

Roman Mold–Diddled Glass

molded glass cup

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "The invention of glassblowing led to an enormous increase in the range of shapes and designs that glassworkers could produce, and the mold-bravado procedure before long developed as an adjunct of free-blowing. A craftsman created a mold of a durable material, normally broiled clay and sometimes wood or metallic. The mold comprised at least two parts, so that it could be opened and the finished product within removed safely. Although the mold could be a unproblematic undecorated foursquare or round form, many were in fact quite intricately shaped and decorated. The designs were usually carved into the mold in negative, and then that on the glass they appeared in relief. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Fine art, Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, Oct 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

"Next, the glassblower—who may not take been the aforementioned person as the mold maker—would blow a gob of hot glass into the mold and inflate it to prefer the shape and design carved therein. He would then remove the vessel from the mold and go along to work the drinking glass while nevertheless hot and malleable, forming the rim and adding handles when necessary. Meanwhile, the mold could be reassembled for reuse. A variation on this procedure, called "pattern molding," used "dip molds." In this procedure, the gob of hot glass was first partly inflated into the mold to prefer its carved pattern, and then removed from the mold and complimentary-diddled into its last shape. Pattern-molded vessels developed in the eastern Mediterranean, and are usually dated to the fourth century A.D. \^/

"While a mold could be used multiple times, it had a finite life span and could be utilized only until the ornamentation deteriorated or information technology broke and was discarded. The glassmaker could obtain a new mold in two means: either a completely new mold would be fabricated or a copy of the start mold would be taken from one of the existing glass vessels. Therefore, multiple copies and variations of mold series were produced, as mold makers would often create 2d-, 3rd-, and even 4th-generation duplicates as the need arose, and these tin can be traced in surviving examples. Considering clay and glass both compress upon firing and annealing, vessels made in a later-generation mold tend to be smaller in size than their prototypes. Slight modifications in design caused by recasting or recarving can also be discerned, indicating the reuse and copying of molds. \^/

"Roman mold-blown drinking glass vessels are particularly attractive because of the elaborate shapes and designs that could be created, and several examples are illustrated here. The makers catered to a broad variety of tastes and some of their products, such as the popular sports cups, may even exist regarded equally gift pieces. However, mold-blowing also allowed for the mass production of plain, utilitarian wares. These storage jars were of uniform size, shape, and volume, profoundly benefiting merchants and consumers of foodstuffs and other goods routinely marketed in glass containers. \^/

Hole-and-corner Chiffonier and the National Archaeological Museum in Naples

The National Archaeological Museum in Naples is one of the largest and best archeological museums in the globe. Located with a 16th century palazzo, it houses a wonderful collection of statues, wall paintings, mosaics and everyday utensils, many of them unearthed in Pompeii and Herculaneum. In fact, most of the outstanding and well-preserved pieces from Pompeii and Herculaneum are in the archeological museum.

Among the treasures are majestic equestrian statues of proconsul Marcus Nonius Balbus, who helped restore Pompeii subsequently the A.D. 62 earthquake; the Farnese Bull, the largest known ancient sculpture; the statue of Doryphorus, the spear bearer, a Roman re-create of ane of classical Hellenic republic's nigh famous statues; and huge voluptuous statues of Venus, Apollo and Hercules that bear witness to Greco-Roman idealizations of strength, pleasure, beauty and hormones.

The well-nigh famous work in the museum is the spectacular and colorful mosaic known both as the Battle of Issus and Alexander and the Persians . Showing Alexander the Great battling King Darius and the Persians," the mosaic was made from 1.5 million different pieces, almost all of them cut individually for a specific identify on the motion-picture show. Other Roman mosaics range from simple geometric designs to breathtaking circuitous pictures.

Too worth expect are the most outstanding artifacts plant at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum are located here. The about unusual of these are the dark bronze statues of water carriers with chilling white eyes fabricated of glass paste. A wall painting of peaches and a glass jar from Herculaneum could easily be mistaken for a Cezanne painting. In another colorful wall painting from Herculaneum a dour Telephus is being seduced by a naked Hercules while a panthera leo, a cupid, a vulture and an angel expect on.

Other treasures include the statue of an obscene male person fertility god eying a bathing maiden four times his size; a beautiful portrait of a couple property a papyrus gyre and a waxed tablet to show their importance; and wall paintings of Greek myths and theater scenes with comic and tragic masked actors. Make sure to check out the Farnese Loving cup in the Jewels drove. The Egyptian collection is ofttimes closed.

The Hole-and-corner Cabinet (in National Archaeological Museum) is a couple of rooms with erotic sculptures, artifacts and frescoes from aboriginal Rome and Etruria that were locked away for 200 years. Unveiled in the year 2000, the ii rooms comprise 250 frescoes, amulets, mosaics, statues, oil laps," votive offerings, fertility symbols and talismans. The objects include a second-century marble statute of the mythological effigy Pan copulating with a caprine animal institute at the Valli dice Papyri in 1752. Many of the objects were found in bordellos in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The collection began with as a royal museum for obscene antiques started by the Bourbon Rex Ferdinand in 1785. In 1819, the objects were moved to a new museum where they were displayed until 1827, when it was closed after complaints by a priest that descried the room equally hell and a "corrupter of the morals or minor youth." The room was opened briefly later Garibaldi set a dictatorship in southern Italian republic in 1860.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Eatables

Text Sources: Cyberspace Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Artifact sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; "Outlines of Roman History" past William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\; "The Private Life of the Romans" past Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Visitor (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian mag, New York Times, Washington Mail service, Los Angeles Times, Alive Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" past Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" past Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, "World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); "History of Warfare" by John Keegan (Vintage Books); "History of Fine art" by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, Due north.J.), Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018

Which Metalworking Technique Was Used To Decorate Bronze Etruscan Cistae,

Source: https://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub399/entry-6332.html

Posted by: clarkrinstall.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Metalworking Technique Was Used To Decorate Bronze Etruscan Cistae"

Post a Comment